Source: TradingView, CNBC, Bloomberg, Messari

Let’s get Token Market Cap Discussions Right

Earlier this year, I published

“12 crypto hills that I will die on”, which pretty much covers everything that we at Arca feel incredibly strongly about regarding both current misinformation and the future of digital assets. One of the topics discussed was how services that report crypto data, specifically Coingecko and Coinmarketcap, are often incorrectly calculating market cap. In our write-up, we wrote:

“Fully-diluted value (FDV) and market cap are used incorrectly by everyone in crypto. This is not a hard concept, and yet CoinGecko, Messari, CoinMarketcap and every other site dedicated to listing crypto assets and prices are doing this incorrectly."

- Adjusted Market cap = Based on the total amount of tokens outstanding (including locked tokens sold to VCs, tokens owned by the team, and employees)

- Float = based on the amount actually trading (which excludes locked tokens or tokens that are restricted from trading or lost)

- FDV = Based on the total amount that COULD be issued (i.e. max supply, including unissued tokens sitting in the company or project’s Treasury). FDV is essentially infinite, just like it is infinite for companies' stock and debt, since any company COULD, in theory, issue more debt and equity at any point. The market’s focus on FDV is just delusional, as most of these tokens will NEVER be issued to the market.”

When we wrote this, the digital assets market was still focused on Layer-1 protocols with massive inflation and decentralized gibberish with little to no value drivers. However, over the past four months, the best-performing assets in the market have been those with real financial value, and as such, many are starting to care about market capitalization and total supply. Said another way, financial metrics like supply don’t matter when you’re just trading memes, dreams, and TAM, but it does matter when you are trying to figure out true valuations. And most are now trying to figure out valuations using incorrectly reported metrics. Therefore, as an industry, we must address and rectify this issue.

Currently, there is a growing group of funds/research outlets that are creating new market cap and FDV methodologies, including (but not limited to) Blockworks, Theia, Pantera, Asymmetric, Coinfund, DACM, Modular and Defiance.

As one of the more outspoken voices in token fundamental value investing, we’d like to re-enter the discussion and delve deeper into what we believe should be the market standard for calculating supply and market caps.

Our Definitive Guide to Adjusted Market Cap and Supply

Crypto and TradFi are starting to converge, and while there are a lot of areas in which crypto can improve upon TradFi methodologies, financial metrics is not one of them. The old TradFi methodologies work great.

Essentially, when a company is formed, it is required to issue an arbitrary number of shares of stock, and 100% of these shares are usually owned by the founders on day one. Very quickly, though, these shares may start to get sold to investors and may be distributed to employees. Whether you become a public company or stay private, a company always has the ability to issue more shares, or buyback shares. There is a standard framework for understanding and defining share counts, market cap, and float:

- Authorized Shares - The total number of shares a company is legally allowed to issue, as specified in its corporate charter. This number is sort of irrelevant, though, because it is easy to change.

Authorized shares = Issued shares + Unissued shares

- Issued Shares - The total number of shares that have ever been issued to investors, including those held by the public, insiders, and the company itself (in its Treasury).

Issued Shares = Outstanding Shares + Treasury Shares

- Outstanding Shares - The shares currently held by all shareholders, excluding shares held in treasury.

Outstanding Shares = Issued Shares - Treasury Shares

- Treasury Shares - Shares that were issued and later repurchased by the company, or shares never issued but held in reserve. NOTE: Treasury shares are not considered “outstanding” and don’t get voting rights or dividends.

- Float (Free Float) - The number of shares available for public trading — excludes closely held shares (e.g., by insiders, executives, or long-term strategic holders).

Float = Outstanding Shares - Restricted/Locked Shares

- Market Capitalization - The total market value of a company’s outstanding shares.

Market Cap = Share Price × Outstanding Shares

Most investors tend to focus on market cap when doing valuation work, and as you can see, the market cap ignores a lot of shares that are not relevant for figuring out TODAY’S value of a stock. You don’t need to include shares that may or may not ever be issued (sold or distributed), and you don’t need to count shares that have been retired (Treasury). If you were trying to draw a parallel to the current (and vastly incorrect) crypto methodology:

- Authorized shares are what most people use to calculate a token’s Fully Diluted Value (FDV), which is including way too much irrelevant information

- Outstanding shares, less locked tokens owned by VCs and the team, less staked tokens, is what most people use to calculate “circulating supply”, and they use that to determine market cap. However, in reality, this number is much closer to the token’s float than it is to its market cap.

Here are the definitions given by CoinGecko, one of the leading sites for token research. Many other sites use a similar methodology. As you can see, this represents a clear deviation from the standard method used by the stock market to calculate market capitalization.

Source: CoinGecko

Neither of these is fully correct. As a result, token market cap is often calculated incorrectly using the float (too restrictive) or using the FDV (too inclusive), but it ignores the most important information. The most important information is not how many tokens are available for trading (float), nor is it how many tokens could, in theory, be issued (FDV) if they are unlikely to ever be issued. What matters is how many tokens are currently outstanding, and that is a metric that is often purposefully, or negligently, hidden from the market.

We need a more effective methodology to account for the number of tokens actually issued, the number outstanding, and the number held back by the Treasury. This methodology didn’t matter when all tokens were Bitcoin, or Bitcoin forks/clones. However, now that we have tokens issued by various issuers (protocols, companies, and individuals) and tokens with different supply features (inflation, amortization, and buybacks), as well as tokens that may or may not have unlocks, it is essential to differentiate. And once again, many of the exchanges, data providers, market makers, OTC dealers, and token issuers are complicit in hiding this information to obfuscate the truth.

So we introduce a new term – Adjusted Market Cap. And to start to calculate it, let’s recognize a very simple fact.

Float ≤ Adjusted Market Cap ≤ FDV

That is a constant. The float and the adjusted market cap can be equal, but the float can never be greater than the adjusted market cap. Similarly, the adjusted market cap and FDV can be the same, but the market cap can never be greater than the FDV (or total supply).

We’ve provided a new table to help determine what we believe should be included in Float, Adjusted Market Cap, and FDV.

Source: Arca Internal Methodologies\

Basically, float and FDV are easy. If the token is currently issued, unlocked, tradable by the public (i.e. in circulation), and is NOT still owned by the corporate or protocol treasury, then it is part of the float. If the token exists (has been minted) and has not been burned (fully retired), it is part of the FDV. But adjusted market cap is more nuanced. Adjusted Market Cap relies on known information. For example, if an airdrop is loosely promised at some point, it is NOT part of the Adjusted Market Cap. However, if a set date and time for distribution have been established, meaning there is no longer subjectivity involved, then it is part of the Adjusted Market Cap, even if it has not been distributed yet, and is not part of the float. This applies to any ecosystem allocations, incentives, grants, and R&D spent via tokens as well. Just because it CAN be issued, does not mean it HAS BEEN or WILL BE issued. It is only counted as part of the adjusted market cap when it becomes established and known.

On the other hand, any tokens issued to private investors, regardless of whether they are unlocked or not, ARE INCLUDED in the adjusted market cap. These tokens are known to be owned by someone other than the protocol/corporate treasury and need to be included in any valuation techniques, even if they are not available for trading yet (part of the float). The same applies to advisor tokens and team tokens.

Let’s look at a few examples:

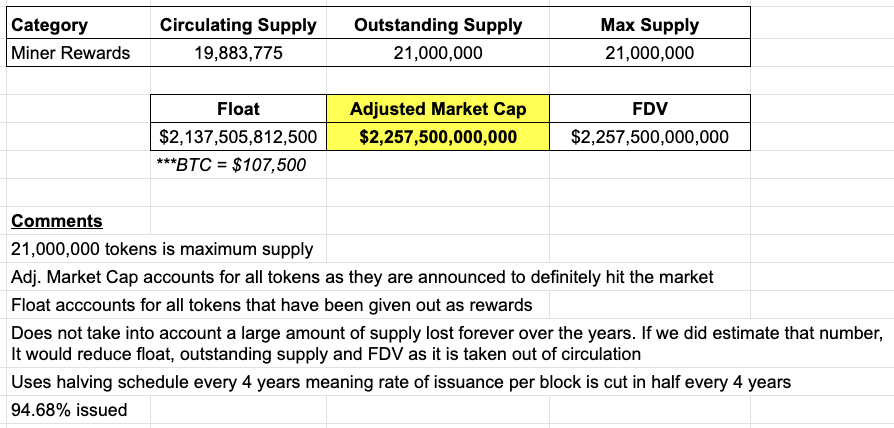

Bitcoin (BTC)

Bitcoin is very straightforward, where the Float, Adjusted Market Cap and FDV are all pretty similar. We know the max supply amount that can be issued (which leads to FDV), but because we know exactly when and how those will be distributed via a known inflation schedule, it is also part of the outstanding supply (which leads to adjusted market cap). You need to multiply the entire 21 million supply of tokens by the price to determine the adjusted market cap. But the circulating supply only includes the coins that have actually been mined and distributed thus far (which leads to a smaller float).

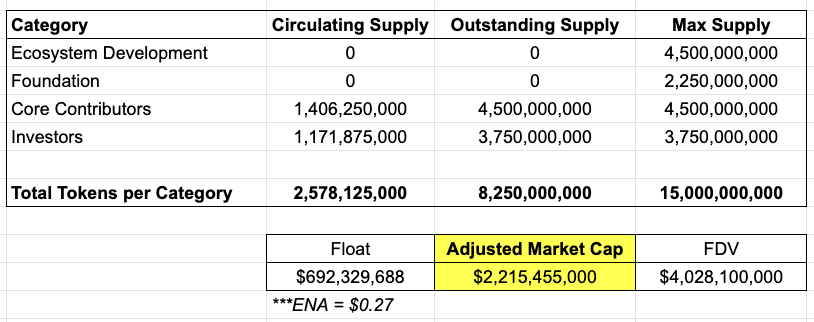

Ethena (ENA): Ethena is less straightforward. Because it is basically a company, you have to remove the tokens that have not been assigned or issued yet from the outstanding supply. Using the Max supply to calculate FDV would make incorrect assumptions about how tokens that are currently unallocated or unissued will get allocated, and using the circulating supply to calculate float incorrectly ignores a ton of tokens that are already owned by investors but are currently locked. The Adjusted Market Cap is the correct number to use, and it falls between the market caps that are most often cited (see CoinGecko).

Source: Arca Estimates using a variety of data sources

Source: Arca Estimates using a variety of data sources

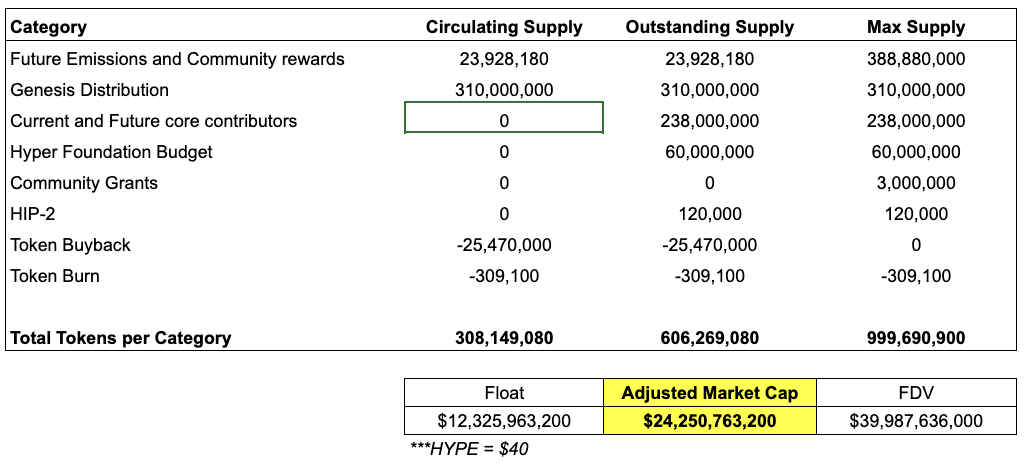

Hyperliquid (HYPE): Hyperliquid’s valuation is one of the more polarizing discussions among analysts, largely due to the massive discrepancy between Float and FDV. However, neither of these metrics is the right one to use, and the correct adjusted market cap is likely somewhere in the middle. Because Hyperliquid has a large number of tokens that are loosely earmarked for rewards or airdrops (without any specific allocation), and because they have bought back many tokens into their assistance fund, using either of these extremes is woefully inaccurate. Further, some of these buybacks are held at the Treasury, whereas some are burned (and taken fully out of the calculation). Fees on spot trading Hyperliquid-native tokens and HyperEVM gas fees are burned. The adjusted market cap ignores most of these tokens because they are unlikely to remain outstanding (or at least reasonable assumptions cannot be made about their status). A significant part of the reason why many investors never bought LEO, BNB, or OKB was that it appears they did not understand how many tokens were being bought back using revenue, and therefore overestimated the market cap (similar to what many are doing with HYPE). When you have both inflationary rewards and buybacks, you have to do more calculations than just looking at one end of the extreme.

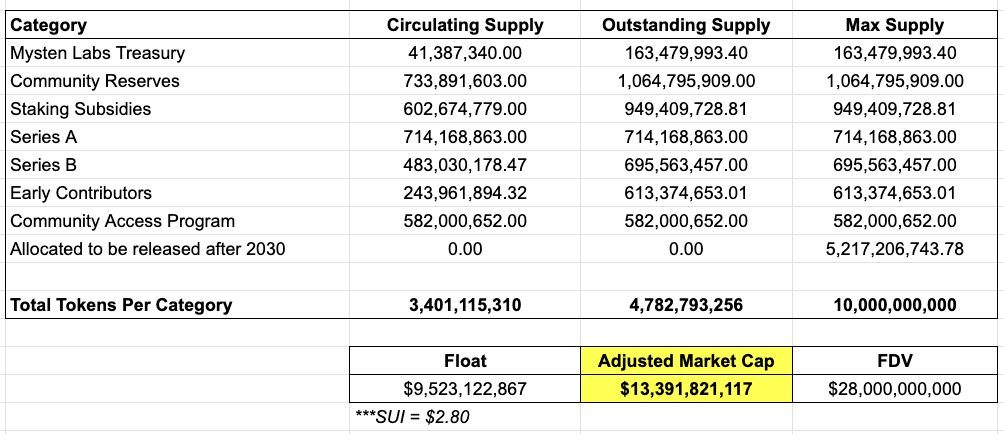

Source: Arca Estimates using a variety of data sources\Sui (SUI): Sui is a good example of a highly inflationary protocol, with lots of locked tokens, where Max Supply is way greater than the outstanding supply, which is way greater than the circulating supply. If you look at

CoinGecko for example, they only list the float at $9.5 bn, and the FDV at $28B, but the adjusted market cap of $13.5B is likely much more accurate.

Source: Arca Estimates using a variety of data sources

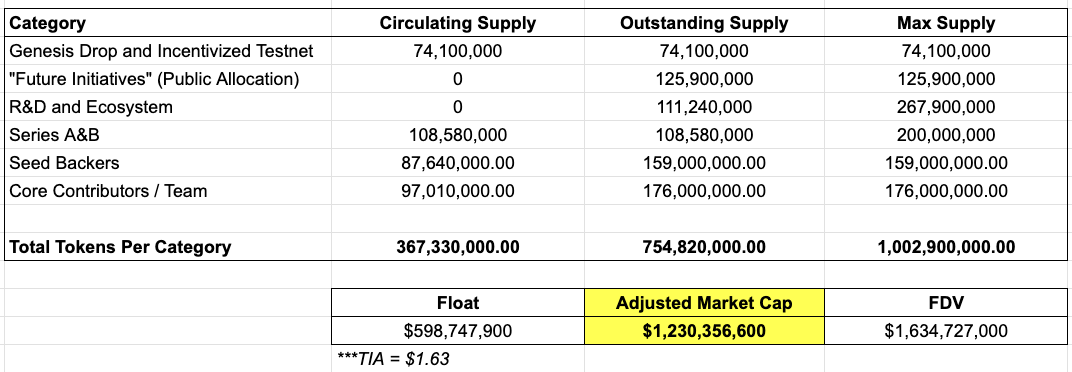

Source: Arca Estimates using a variety of data sourcesCelestia (TIA): looks similar to SUI above, and once again, we found errors in how

CoinGecko calculates this. It is difficult to tell what exactly has been done regarding R&D and Ecosystem as it pertains to grants/allocations – the project easily could have paid out a lot of this, and therefore it would be part of the circulating supply. And therein lies the difficulty with providing standardized data like this.

Source: Arca Estimates using a variety of data sources

Source: Arca Estimates using a variety of data sources

Some of the information needed to calculate this type of data accurately is difficult to obtain and figure out. Because a token can be publicly traded without disclosures set forth by regulators, it is currently up to the token issuers, or the data providers, or the exchanges to ensure that this information is accurate before putting it out there to the public. OR, it is up to the entire community of on-chain sleuths (ourselves included), to uncover the correct information and get it out there to the public, so that the data providers make adjustments. But that’s not a perfect system.

What we need to do is create a standard that every token issuer needs to adhere to in order to get their token listed on an exchange or to trade via a DEX. And if enforcement is not possible, then social pressure needs to be the standard, meaning the entire industry warns investors not to touch tokens that don’t transparently update this information.

This is an incredibly important data point, and an easy standard to adhere to. Let’s create the standard, and get this right for the sake of this industry.